In many asphalt mixing plant projects, environmental monitoring results are often ideal in the initial stages of operation. Equipment is configured correctly, parameters are normal, and emission data fully meet requirements. However, as production load increases and operating time lengthens, emission fluctuations begin to appear, even becoming more frequent. Faced with this situation, the problem is often simplified to whether the environmental protection equipment is inadequate.

In fact, in actual engineering, emissions are never solely determined by the quality of the equipment. They are the engineering manifestation of the long-term combined effects of structural design, flue gas path, and system sealing. When these fundamental conditions continuously change during operation, emission fluctuations are almost inevitable.

Why Emission Instability Has Become a Common Challenge in the Industry?

Over the past few years, initial compliance followed by subsequent fluctuations has become a common experience for asphalt mixing plants in environmental protection operations. Multiple industry surveys and project operation feedback show that more than half of the in-service mixing plants experience varying degrees of emission fluctuations after a period of continuous operation, with the problems often concentrated within 6-18 months after commissioning. This is not a problem of individual equipment or a single brand, but rather a systemic result of multiple industry changes.

Changes in Emission Requirements: From Result Compliance to Process Stability

According to feedback from project operations and maintenance in multiple locations, over 60% of the problems identified during recent environmental inspections did not originate at the moment of testing, but rather stemmed from emission fluctuations recorded during operation. Some projects, even those meeting test standards, were still required to rectify issues due to unstable operational data.

- The change lies in the shift in environmental regulatory focus from one-time test results to a comprehensive assessment of the continuous operation and emission fluctuations of asphalt mixing plants. Tolerance for outliers and short-term fluctuations has significantly decreased.

- The impact is that under this regulatory logic, emissions are no longer considered merely a matter of compliance at a single test moment, but rather a long-term operational indicator that needs to remain stable throughout the entire production cycle.

- The ultimate result is that even if equipment meets environmental standards during testing, frequent or significant emission fluctuations during actual production are easily identified as insufficient system stability, rather than being considered an occasional problem.

Changes in Equipment Operating Cycles: Long-Term Operation Becomes the Norm

Industry statistics show that in most medium and large-scale projects, asphalt mixing plants generally operate continuously for more than 8–12 hours per day. Some highway or airport projects even maintain near full-load operation for a long time. This operating condition is significantly higher than the operating intensity in the early design verification stage.

- The change lies in the fact that with the expansion of project scale and changes in production organization methods, more and more asphalt mixing plants need to operate continuously for extended periods under high-load conditions.

- The impact is that equipment is no longer in an ideal short-cycle, low-intensity operating state, but rather subjected to the combined effects of high temperatures, vibrations, thermal expansion and contraction, and negative pressure environments over long periods.

- The ultimate result is that structural deviations and seal degradation that are not obvious during initial operation will gradually become apparent during long-term operation, directly affecting emission stability.

Changes in equipment design verification focus: More emphasis on commissioning than long-term operating conditions

According to project failure statistics, more than 70% of emission anomalies did not occur in the early stages of production, but rather occurred after 6 months to 1 year of operation. Most of the problems were related to loose interfaces, structural deformation, or decreased sealing performance.

- The change lies in the fact that during the equipment design, manufacturing, and delivery phases, the industry generally focuses more on whether the equipment can be successfully commissioned and meet initial emission requirements, while lacking systematic verification of the structure and sealing condition after long-term operation.

- The resulting impact is that equipment often performs stably in the initial delivery phase, but this performance reflects the state under ideal conditions rather than the actual operating capacity under complex conditions.

- The ultimate result is that when the equipment enters a long-term, high-load operation phase, emission stability begins to decline, resulting in a common phenomenon of initial compliance followed by later fluctuations.

Changes in system complexity: Emissions are more easily amplified

In the completed analyses of emission anomaly cases, more than half of the problems did not originate in the dust collector itself, but rather in pipe interfaces, structural connection nodes, or system pressure regulation points. These problems are often difficult to detect directly during single-point inspections, but they will continue to amplify in operational data, eventually triggering emission anomalies.

- The change lies in the fact that the emission system of an asphalt mixing plant involves multiple equipment, pipelines, and connection nodes, with a complex overall structure and high coupling between various components.

- The resulting impact is that any local change can be transmitted through the system, affecting the overall operating status, and the problem often does not directly appear at the emission end.

- The end result is that emissions instability has gradually evolved from a problem in individual projects into a systemic challenge faced by the entire industry.

Emission System: Operation and Key Characteristics

Faced with the dilemma of initial compliance followed by subsequent fluctuations, simply looking at the performance of a single device is no longer sufficient. We must look at the emissions issue from a more fundamental perspective—how the entire emissions system operates, and how each link, each pipe, and each interface determines long-term stability. To truly understand why emissions fluctuate, we must first understand the system’s operating logic and inherent characteristics, analyzing it as a whole, rather than focusing solely on end-point devices.

How does the emission system operate?

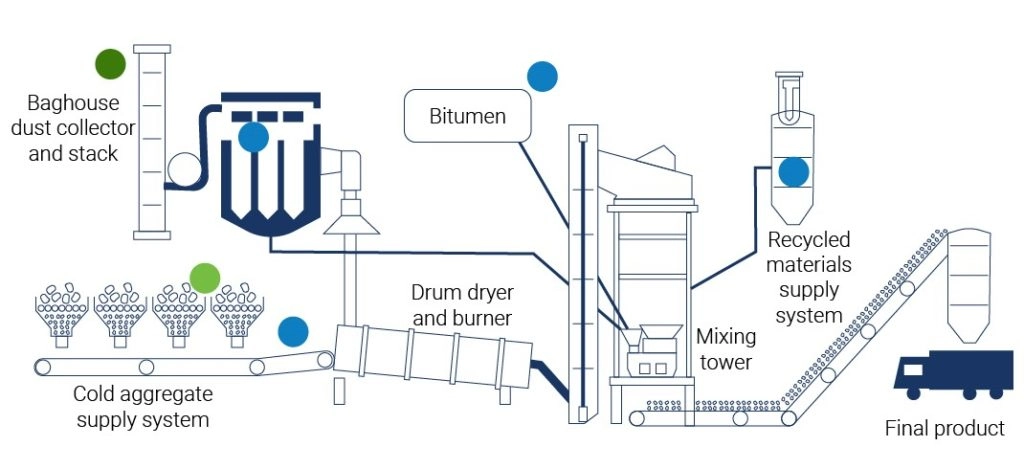

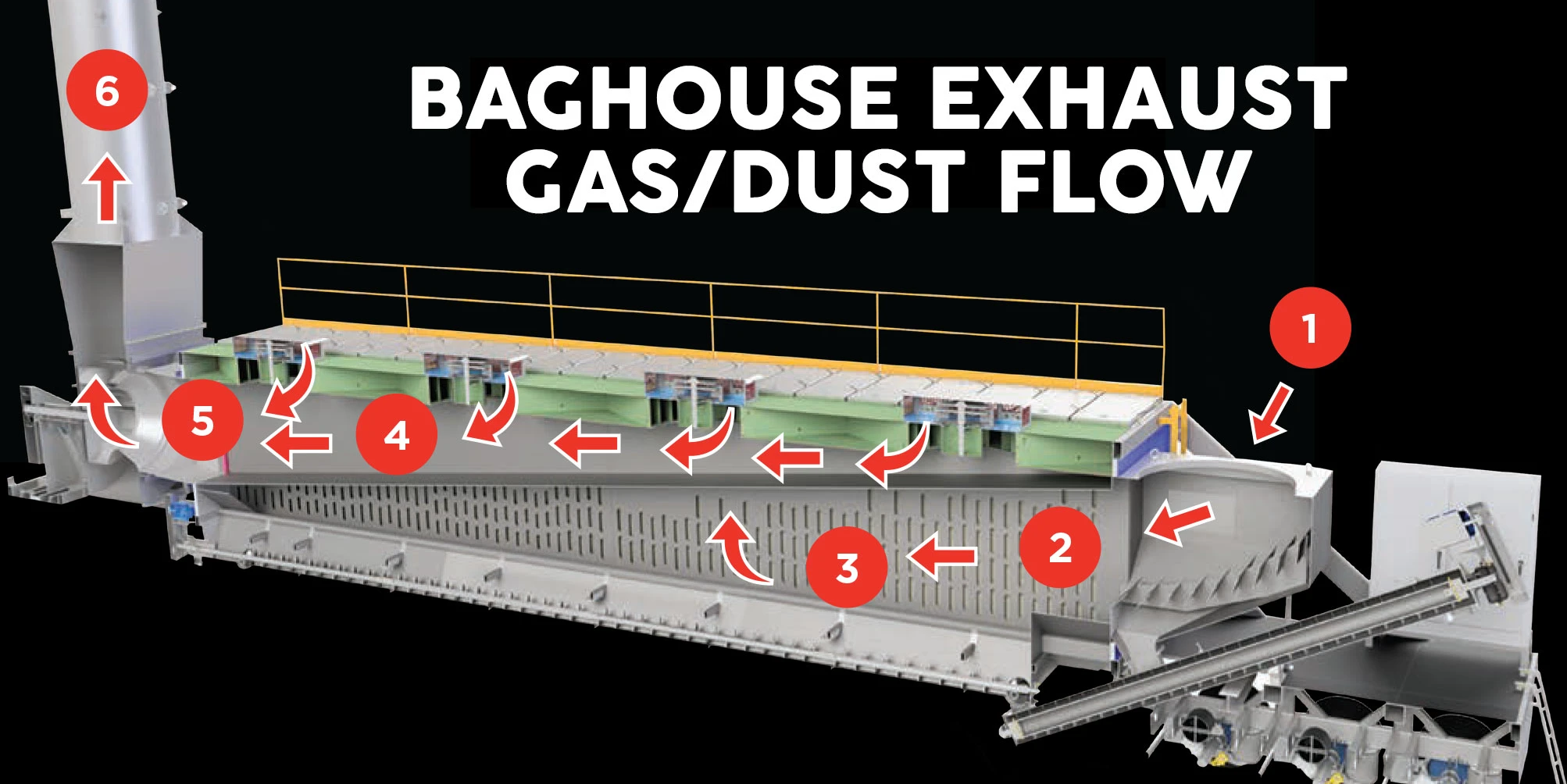

The emission system of an asphalt hot mix plant is not an independent device, but a process chain that runs through the core production stages. Its operation begins with heat generation and ends with the discharge of purified gas. The process can be clearly divided into the following sequential stages:

Starting Point: Flue Gas Generation and Primary Mixing

- The drying drum and burner are the starting point of the system. The burner generates a high-temperature flame, heating the aggregate and evaporating moisture within the drying drum. The high-temperature flue gas generated in this process is the carrier for all subsequent processes.

- Core Function: This determines the initial flue gas temperature, flow rate, and initial dust load.

Transmission: Flue Gas Collection and Transportation

- The high-temperature flue gas, carrying evaporated moisture and fine dust separated from the aggregate, leaves the drying drum.

- Core Function: The piping system forms a closed transmission network. It guides the flue gas to the next stage through negative pressure. Its design directly affects airflow resistance, velocity, and whether dust will settle midway.

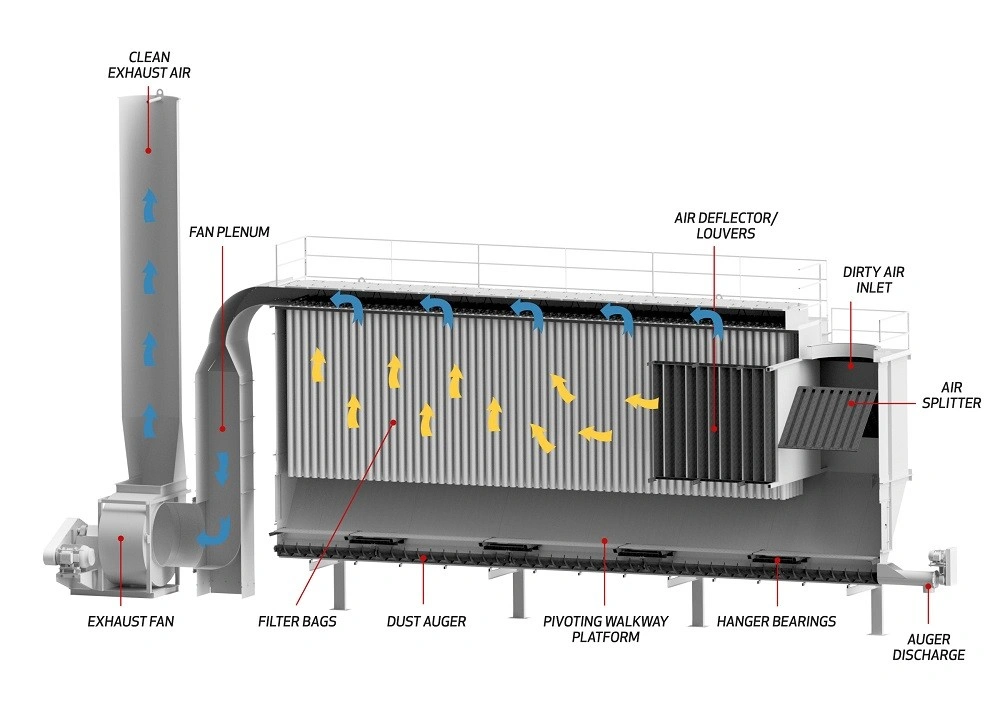

Core: Pollutant Separation and Capture

- The flue gas enters the bag filter (core purification equipment). Dust-laden flue gas passes through filter bags, where dust is trapped on the filter bag surface, forming a filter cake; the purified gas then passes through the filter bags.

- Core Function: This is the key step in separating pollutants (dust) from clean gas. Its efficiency is the technological foundation for achieving emission standards.

Power Source: The Heart of the System

- The induced draft fan, located after the dust collector, is the power source for the entire flue gas path. It continuously draws air, establishing and maintaining a stable negative pressure within the system, ensuring that the flue gas flows along the designed path and overcomes all resistance.

- Core Function: Providing power and controlling the airflow balance and pressure distribution of the entire system.

Emission data is the status display at the end of this process chain. Flue gas flows sequentially through: combustion generation → duct transportation → dust removal and purification → fan-driven discharge. Changes in the status of any of these stages will alter the flue gas conditions flowing downstream and ultimately affect the final emission results.

Three Systemic Characteristics of Emission Systems

- Full-Process Interconnectivity: The emission concentration at the end-of-pipe monitoring point is the actual result of the combined effects of all the aforementioned links. Every upstream process parameter, such as changes in drum temperature and airflow, will transmit and affect the end-of-pipe result.

- Structural Complexity and Node Vulnerability: From the drum to the chimney, the flue gas path is tens of meters long, connecting multiple large pieces of equipment in series and linked by numerous flanges, locking devices, access doors, and expansion joints. Each connection point is a potential leak point or a point of resistance variation.

- Dynamic Coupling and Amplification Effect: The subsystems are tightly coupled through airflow and pressure, forming a dynamically balanced whole. The operating point of the induced draft fan depends on the total system resistance, which in turn is determined by the condition of each section of pipeline and each piece of equipment.

From the drying drum to the induced draft fan, the emission system of an asphalt mixing plant is a tightly connected process chain, with each link affecting downstream airflow, temperature, and dust conditions. The full-process interconnectivity, structural complexity, and dynamic coupling of the subsystems mean that emission stability is not the result of a single piece of equipment, but rather the result of the entire system working collaboratively. Only by understanding these operating logics and inherent characteristics can we truly see the root cause of emission fluctuations.

Structural Design: The Physical Basis of Emission Stability

Having understood the emission system as a series of dynamically coupled processes, the issue of emission stability is no longer merely a matter of equipment selection; its stability is largely influenced by structural design. The flue gas path, equipment interfaces, piping layout, support rigidity, and the arrangement of system nodes all directly determine the stability of airflow, pressure, and dust distribution. An unreasonable structure is often the root cause of emission fluctuations and subsequent instability.

Flue Gas Path Structure – Airflow Turbulence Leading to Fluctuations

- Sharp Bends and Abrupt Changes in Cross-Section: Sharp bends and changes in cross-section create eddies and stagnant flow, causing dust to deposit and be re-entrained during airflow fluctuations, resulting in instantaneous emission fluctuations.

- Uneven Distribution of Inlet Air and Feed: Uneven interface layout leads to uneven airflow distribution within the dust collector and ductwork, causing some filter bags to be overloaded and resulting in significant fluctuations in dust removal efficiency.

- Path Length and Accumulated Flow Resistance: Long paths increase the total system resistance, and local disturbances easily accumulate and amplify to the final emission level.

Equipment Interfaces and Support Structure – Leakage and Pressure Disturbances

- Interface Misalignment or Loosening: Slight misalignment of flanges, bolts, or welds can cause localized air leakage, introducing cold air or disturbing the airflow, affecting the downstream flue gas velocity.

- Support Fatigue and Vibration: Long-term vibration or insufficient support can cause interface loosening, fretting wear, or structural deformation, gradually accumulating into emission fluctuations.

- Effects of Thermal Expansion and Contraction: The temperature difference between the high-temperature drum and the ambient-temperature dust collector changes the shape of the duct and interfaces, altering local flow resistance and pressure distribution.

Number of System Nodes – Sensitivity and Amplification Effects

- Too Many Nodes: Each additional flange, expansion joint, or access door increases the potential for leaks or changes in flow resistance, making the system more sensitive to local variations.

- Series Complexity: Connecting multiple devices in series can amplify local pressure or flow abnormalities, affecting the stability of end-of-pipe emissions.

- Accumulation of Local Problems: When pipelines are too long or poorly laid out, small problems gradually accumulate within the system, eventually manifesting as fluctuations in end-of-pipe emissions.

Pipeline and Dust Collector Interface Layout – Local Deposition and Uneven Filter Bag Load

- Inappropriate Interface Location: Causes dust to accumulate locally in the pipeline or at the dust collector inlet, which is then stirred up by airflow fluctuations, resulting in emission fluctuations.

- Uneven Arrangement of Inlets or Baffles: Causes uneven filter bag loads, with some filter bags overloaded and prematurely worn, while others are underutilized.

- Uneven Exhaust Distribution: Affects the uniformity of airflow within the dust collector, reducing overall dust removal efficiency and increasing end-of-pipe emission fluctuations.

Support and Rigid Structures – Potential Risks to Long-Term Stability

- Uneven support arrangement: Vibration amplifies local interface displacements, leading to long-term instability in the flue gas flow field and pressure distribution.

- Fatigue in structurally weak areas: Long-term vibration causes weld cracking, flange loosening, or micro-deformation of pipelines, resulting in system leaks.

- Lack of dynamic compensation: The structure cannot adapt to temperature changes or vibration, leading to changes in local flow resistance and emission fluctuations.

The stability of an emission system is influenced by multiple factors in its structural design: flue gas path, interfaces and supports, system node layout, dust collector interface layout, and support rigidity. Each of these factors can potentially become a source of emission fluctuations. Understanding these influencing factors and their mechanisms can explain why some asphalt mixing plants initially meet emission standards but experience frequent emission fluctuations after long-term operation.

Sealing: The Key Factor for Long-Term Emission Stability

In emission systems, sealing is crucial for long-term stability. It not only affects emissions during a single operation but also determines the system’s performance under long-term, high-load, and thermal cycling conditions. The key is not the presence of leaks, but the ability to maintain leak-free operation over the long term. Sealing issues gradually manifest over time due to thermal stress and vibration, and are amplified through the system, impacting overall emission stability. The following are some key influencing factors and their analysis:

Number and Distribution of Sealing Points

- More interfaces, higher failure probability: The more interfaces on pipe flanges, expansion joints, inspection doors, and dust collectors, the more likely each one is to become a source of leakage, increasing the overall system leakage risk.

- Dynamic parts are more prone to failure: Thermal expansion and contraction, vibration, or frequent equipment start-ups and shutdowns can make dynamic interfaces such as expansion joints and rotary valves leak points, affecting local pressure and airflow stability.

- Uneven distribution leads to local pressure disturbances: Sealing points concentrated in the same area can create local airflow disturbances, amplifying the impact on downstream emissions.

Sealing Material Durability

- High-temperature environments accelerate aging: Long-term high temperatures can cause sealing materials to harden and become brittle, reducing sealing performance and gradually increasing leakage.

- Oil, gas, and dust erosion: Oil, asphalt residue, and dust in flue gas can adhere to the sealing surface, reducing friction performance or damaging the seals.

- Material fatigue and performance degradation: Seals subjected to pressure, vibration, and thermal cycling over a long period of time will gradually develop micro-cracks or deformation, leading to a decrease in system sealing performance.

Amplification Effects of Localized Seal Failure

- Even minor leaks can affect the overall system pressure: Even tiny leaks can alter the negative pressure distribution of the system, causing changes in flue gas velocity and path.

- Localized leaks cause filter bag load fluctuations: Leaking areas can cause some filter bags to experience decreased or increased loads, leading to uneven dust removal efficiency and affecting end-point emissions.

- System coupling effect amplifies fluctuations: Through airflow and pressure coupling, disturbances caused by localized leaks are transmitted and amplified, manifesting as overall emission fluctuations.

Difficulty in Seal Maintenance

- Interfaces difficult to inspect regularly: Seals located at high altitudes, in narrow spaces, or in complex structures are easily overlooked. Small leaks accumulate over time, ultimately affecting overall emissions.

- High maintenance difficulty of dynamic interfaces: Components requiring frequent operation, such as rotary valves and expansion joints, are difficult to maintain and pose a greater risk of seal failure.

- Invisible aging and wear: Micro-cracks or material hardening inside seals are difficult to detect, accumulating slowly over long-term operation and leading to increased system leakage.

How Structural and Sealing Issues Are Amplified During Operation

Structural and sealing issues may be minor and difficult to detect during the design or installation phase, but they can be gradually amplified during long-term operation due to changes in system conditions, operating loads, and the environment, ultimately having a significant impact on emission stability.

High-load continuous production

- Increased pipeline pressure fluctuations: Under high-load operation, increased airflow amplifies pressure differences caused by local structural resistance or minor leaks, leading to significant deviations in flue gas velocity and path.

- Uneven filter bag load: Structural or sealing defects cause some airflow to bypass or concentrate in certain filter bag units, resulting in excessive or insufficient load and reducing overall dust collection stability.

- Dust accumulation and secondary re-entrainment: Under prolonged high-load operation, dust deposited in pipelines is easily agitated by airflow, creating instantaneous emission peaks.

Frequent start-ups and shutdowns

- Thermal expansion and contraction causing interface micro-movements: Frequent start-ups and shutdowns cause rapid temperature changes in rollers and pipelines, leading to micro-movements in interfaces or seals, loosening bolts, and gradual accumulation of leaks.

- Accumulated vibration and impact: Vibrations from equipment start-ups and shutdowns act on the support structure and flange interfaces, gradually amplifying micro-cracks or loosening, causing local seal failure.

- Dynamic changes in airflow path: Frequent start-ups and shutdowns generate pressure fluctuations and instantaneous changes in flow velocity, amplifying initially minor structural defects into significant emission fluctuations.

Drastic Temperature Changes

- Micro-deformation of Pipelines and Interfaces: Alternating hot and cold temperatures cause repeated expansion and contraction of pipes, expansion joints, or dust collector interfaces, gradually altering the sealing condition and flow resistance.

- Transmission of Local Pressure Disturbances: Local leaks caused by thermal stress can be amplified through the negative pressure system, affecting downstream flue gas flow and leading to emission fluctuations.

- Accelerated Material Aging: High temperatures and thermal cycling accelerate the fatigue of sealing materials, causing micro-cracks to expand and accumulate over time, forming significant system leak points.

Long-Term Operation of Negative Pressure Systems

- System Coupling Amplifies Local Problems: The negative pressure system tightly couples the airflow throughout the entire process. Local structural or sealing defects can affect the overall pipeline pressure balance, amplifying end-point emission fluctuations.

- Chain Reaction from Minor Leaks: Even small leaks alter local suction, causing changes in the load on other interfaces or filter bags, creating a chain reaction.

- Pressure Fluctuations Affect Dust Collection Efficiency: Local pressure changes under negative pressure directly affect the working state of the dust collector filter bags, making previously minor problems manifest at the system output.

Structural design and sealing issues do not exist in isolation during operation. High loads, frequent start-stop cycles, temperature variations, and prolonged negative pressure operation can amplify minute defects through pressure, airflow, and coupling effects, ultimately leading to significant emission fluctuations.

Practical Insights into Emission System Design — From Problems to Improvement

Long-term unstable emissions can lead to a series of negative impacts:

- Increased risk of production stoppage: Emission fluctuations may trigger environmental alarms or lead to production stoppages due to exceeding standards, affecting production continuity.

- Environmental penalties and compliance pressure: Instantaneous exceedances or fluctuations in data may be interpreted by regulators as system inadequacy, resulting in fines or rectification.

- Equipment load and maintenance pressure: Unstable airflow and dust distribution accelerate filter bag wear and pipe corrosion, increasing asphalt plant cost.

- Damage to corporate reputation and project continuity: Frequent fluctuations reflect insufficient system stability, affecting the trust of customers and partners.

These real-world pressures suggest that the industry must shift from single-time compliance management to long-term stable management of emission systems. From an engineering perspective, emission system design should have new requirements, mainly in two aspects:

Structural Design Improvements to Reduce Emission Fluctuations

In emission systems, the core of structural design optimization is to ensure that airflow, pressure, and dust transport remain stable throughout the entire process. By reducing resistance fluctuations, optimizing pipeline paths, and strengthening key nodes and supporting structures, the risk of minor structural defects being amplified during long-term operation can be reduced, thus enabling the system to maintain stable emission performance even under dynamic operating conditions such as high loads, frequent start-stops, and temperature changes.

Flue Gas Path Optimization:

- Flow Field Homogenization: Reduce sharp bends and abrupt changes in cross-section; optimize bend curvature and pipe diameter to ensure smooth airflow.

- Reducing Deposition and Secondary Lifting: Optimize the arrangement of dust collector inlets and baffles to prevent dust deposition in pipes or interfaces.

- Lowering Total Path Resistance: Shorten the flue gas flow path to reduce the amplification effect of local disturbances on end emissions.

Interface and Node Optimization:

- Minimizing Interface Number: Reduce the number of flanges, expansion joints, and access doors to lower potential leakage points.

- Strengthening Critical Nodes: Reinforce pressure-bearing and vibration-sensitive interfaces to reduce the risk of fretting wear and loosening.

- Optimizing Node Distribution: Rationally arrange the series sequence of equipment to avoid amplifying local problems through system coupling.

Support and Mechanical Design:

- Optimizing Support Rigidity: Balance the support layout to reduce interface loosening or structural fatigue caused by concentrated vibration.

- Thermodynamic Compensation Design: Install expansion joints or expansion compensation devices to reduce the impact of thermal expansion and contraction on interfaces and pipes.

- Maintenance accessibility design: Ensure that critical structural nodes are easy to inspect and repair, and intervene in minor deformations or loosening in a timely manner.

Sealing Improvements — Ensuring Long-Term Reliability

Optimizing sealing performance focuses on ensuring the integrity and reliability of the system under long-term operating conditions. By rationally arranging sealing points, selecting high-temperature resistant, wear-resistant, and corrosion-resistant sealing materials, and combining maintainability and online monitoring measures, it is possible to prevent minor leaks from being amplified by airflow and negative pressure systems, thereby maintaining a closed flue gas path, stable pressure, and ensuring long-term stable emissions throughout the entire production cycle.

Sealing Point Management:

- Quantity and Layout Optimization: Minimize the number of sealing points, distribute critical interfaces, and reduce local pressure disturbances.

- Dynamic Interface Management: Employ highly reliable sealing solutions for dynamic interfaces such as rotary valves and expansion joints.

- Critical Node Reinforcement: Strengthen sealing points subjected to negative pressure fluctuations and vibrations to reduce the risk of micro-leakage.

Sealing Material Durability:

- High Temperature and Corrosion Resistant Materials: Select sealing materials capable of withstanding flue gas temperatures, oil and gas corrosion, and dust erosion.

- Aging and Fatigue Resistance Design: Materials must maintain elasticity and deformation recovery capabilities over the long term to prevent performance degradation due to long-term vibration and thermal cycling.

- Abrasion Resistance Optimization: Select abrasion-resistant materials for dynamic interfaces and dust abrasion points to extend service life.

Maintenance and Monitoring:

- Accessibility Design: Ensure sealing points are easy to inspect, maintain, and replace, reducing the risk of accumulating hidden leaks.

- Online Status Monitoring: Install pressure, flow, or temperature sensors at critical interfaces to detect even minor leaks promptly.

- Preventive maintenance mechanism: Establish a periodic maintenance plan, replace aging or damaged seals in advance, and avoid long-term fluctuations.

Project-Based Evidence of Structural and Sealing Optimization

In highway, airport, and large-scale municipal projects, asphalt mixing plants typically face long-term, high-load, and heavily regulated operating environments. Multiple engineering practices have shown that targeted optimization of the emission system at the structural and sealing levels results in quantifiable improvements in emission stability and operational performance.

Scenario 1: Highway Project – Continuous High-Load Production

- Project Background: A highway mainline construction project. The mixing plant operates for 10–14 hours daily, with production load consistently near the design limit. Environmental monitoring primarily relies on continuous operation data for evaluation.

- Typical Problems: Emission concentrations briefly increase during load fluctuations; frequent alarms during start-up and shutdown, but no obvious damage to the dust collector itself.

Improvement Measures:

- Optimize the flue gas path between the drying drum and the dust collector, reducing sharp bends and diameter changes.

- Adjust the dust collector’s inlet structure to improve airflow distribution.

- Reinforce high-vibration interfaces.

Results:

- Daily emission concentration fluctuations decreased by approximately 35%–45%;

- The number of over-limit alarms during start-up and shutdown decreased by more than 60%;

- System operating pressure differential fluctuations significantly converged.

Scenario 2: Municipal Road Project – Frequent Start-up and Shutdown Conditions

- Project Background: Urban road or municipal projects with discontinuous production rhythms, frequent equipment start-ups and shutdowns, and significant thermal expansion and contraction.

- Typical Problems: Emissions gradually worsen after a period of operation; filter bag pressure differential rises rapidly, leading to high maintenance frequency.

Improvement Measures:

- Add thermal expansion compensation in the transition zone between high and normal temperatures;

- Optimize pipeline support layout to reduce stress concentration;

- Upgrade materials for easily aging sealing points.

Results:

- Filter bag lifespan extended by approximately 25%–30%;

- Long-term average emission concentration decreased by approximately 10%–15%;

- Annual maintenance man-hours reduced by approximately 20%.

Scenario 3: Long-Term Operation Projects – Pressure on Operation and Maintenance Costs

- Project Background: Long-term service-oriented mixing plant with a long operating lifespan; the owner is concerned with balancing environmental stability and maintenance costs.

- Typical Problems: Frequent minor problems in the emission system; repairs only address the symptoms, not the root cause; emission fluctuations are accompanied by increased maintenance costs.

Improvement Measures:

- Increase safety margins for key structural nodes;

- Standardize the selection of seals and establish a preventative replacement mechanism;

- Improve inspection and maintenance accessibility.

Results:

- Frequency of emissions-related failures decreased by approximately 40%;

- Annual maintenance costs decreased by approximately 15%–25%;

- Emission stability shifted from relying on human intervention to system self-stabilization.

Emission stability reflects the capabilities of a systems engineering approach, not just the performance of a single piece of equipment. Structural design determines the smoothness of airflow, pressure, and dust transport, while airtightness ensures the system remains leak-free under dynamic operating conditions. Through multi-level improvements such as structural optimization, node reinforcement, support compensation, upgraded sealing materials, and maintenance monitoring, the risk of emission fluctuations can be reduced at the source, ensuring long-term system stability and providing a solid guarantee for production continuity, environmental compliance, and corporate reputation.

Environmental Capability as a New Industry Baseline

As the industry’s requirements for emission stability continue to rise, environmental protection capabilities are no longer merely an add-on to meet inspection standards, but rather a core indicator for evaluating the engineering capabilities of an asphalt mixing plant. In this context, structural design and sealing are no longer just details, but key factors determining the long-term stability and emission reliability of the system.

Only by considering these as part of the system’s overall capability can enterprises consistently meet standards under complex operating conditions, ensuring production continuity and corporate reputation, and achieving true long-term environmental protection capabilities.